Every year, governments the world over spend astronomically-large amounts of money. The US federal government spent more than 6.1 trillion dollars in FY2023 alone. Which begs the question: where do we get all that money?

Obviously, the money comes from taxes and bonds. Right?

That's what I thought until I came across a paper in which financial economist Stephanie Kelton (f.k.a. Stephanie Bell), drilled down to the core of a seemingly obvious question: "Can Taxes and Bonds Finance Government Spending?"

In the author's own words, "Both questions seem absurd."[1] But could there possibly be something to this inquiry?

After all, it probably sounded absurd when Galileo and the like began to question the predominant worldview by investigating if the Sun did, in fact, orbit the Earth. (Spoiler alert: it doesn't.) Strange as it may be, perhaps this question has the potential to elucidate new concepts with equally profound implications for our (financial) worldview.

Lets take a look and see.[2]

You can read about Dr. Kelton's own skeptical experience of the topic in her book: The Deficit Myth ↩︎

Any insights here are credited to the author of the paper in view, Stephanie Kelton (f.k.a. Stephanie Bell). Any errors and omissions in the interpretation and representation of the original work are unambiguously my own. If you see something that can be improved— please let me know. ↩︎

"Can Taxes and Bonds Finance Government Spending?" by Stephanie Kelton

In this paper, Kelton zooms out to provide a 30,000-foot view of the banking system and dives deep into how the Treasury and the Fed have worked together for more than a century to ensure that the government is able to do business as usual —make payments and collect taxes— while administering a stable short-term interest rate. Kelton then asks: does the US Treasury coordinate the collection of taxes and bonds with new expenditures out of necessity (as a means of finance) or for some other reason? To get at this question, let's review some key context:

The Fed and the Interest Rate

The Federal Reserve System ('the Fed') is the US central bank which serves as the country's financial scorekeeper. The Fed is the steward of a big balance sheet that allows banks to transact with one another and the government using dollars called "reserves". Reserves, like Federal Reserve Notes —those dollars in your wallet— are booked as liabilities on the Fed's balance sheet meaning that they are an IOU or a promise created by the state.

What's the government's promise, and why do we value it so much?

The government's promise is written on each and every dollar bill:

"This note is legal tender for all debts, public and private"

It may seem like a pretty basic disclaimer, but this promise shows its value when it comes time to settle taxes, fees, or court settlements as required by law. If someone incurs a tax bill (i.e. by earning an income or owning land) they're going to have a hard time extinguishing their debt to the government if they only have pesos, loonies, euros, francs, or crypto. The tax agency only accepts payments denominated in its own currency. It only accepts those promises it issued in the past expressly for the purpose of extinguishing debts, public and private.

In addition to its financial scorekeeping duties, the Fed has been tasked by Congress to do what it can to see that prices are stable and that as many people are employed as possible. In an attempt to fulfill this legal mandate, the Fed is laser-focused on controlling the price that it costs to borrow money. This price (rate of interest) is called the Federal Funds Rate, the cash rate, or more colloquially, 'the interest rate'. This is the interest rate that affects how much money we pay in interest on loans like home mortgages, or how much interest the bank pays you in your savings account. At a high level, this price affects the relative appeal of investing your money in more liquid (easily-exchangable) assets like treasury securities (Treasury Bills and Treasury Bonds) as compared to other financial assets or real-world investments.

How the Fed sets the Interest Rate

The Fed's protocols have evolved with time[3] , but in 1998 when this paper was published —and for more than 160 years— the interest rate was set as banks settled on an agreeable price at which to borrow and lend reserves in what's called the "overnight lending market." By law, banks were required to maintain a certain balance of reserves in proportion to its clients' bank deposits. If a bank was short of this reserve requirement, it would place a bid in the market to borrow reserves from another bank that was interested in lending out the extra reserves it had on hand in exchange for some return.

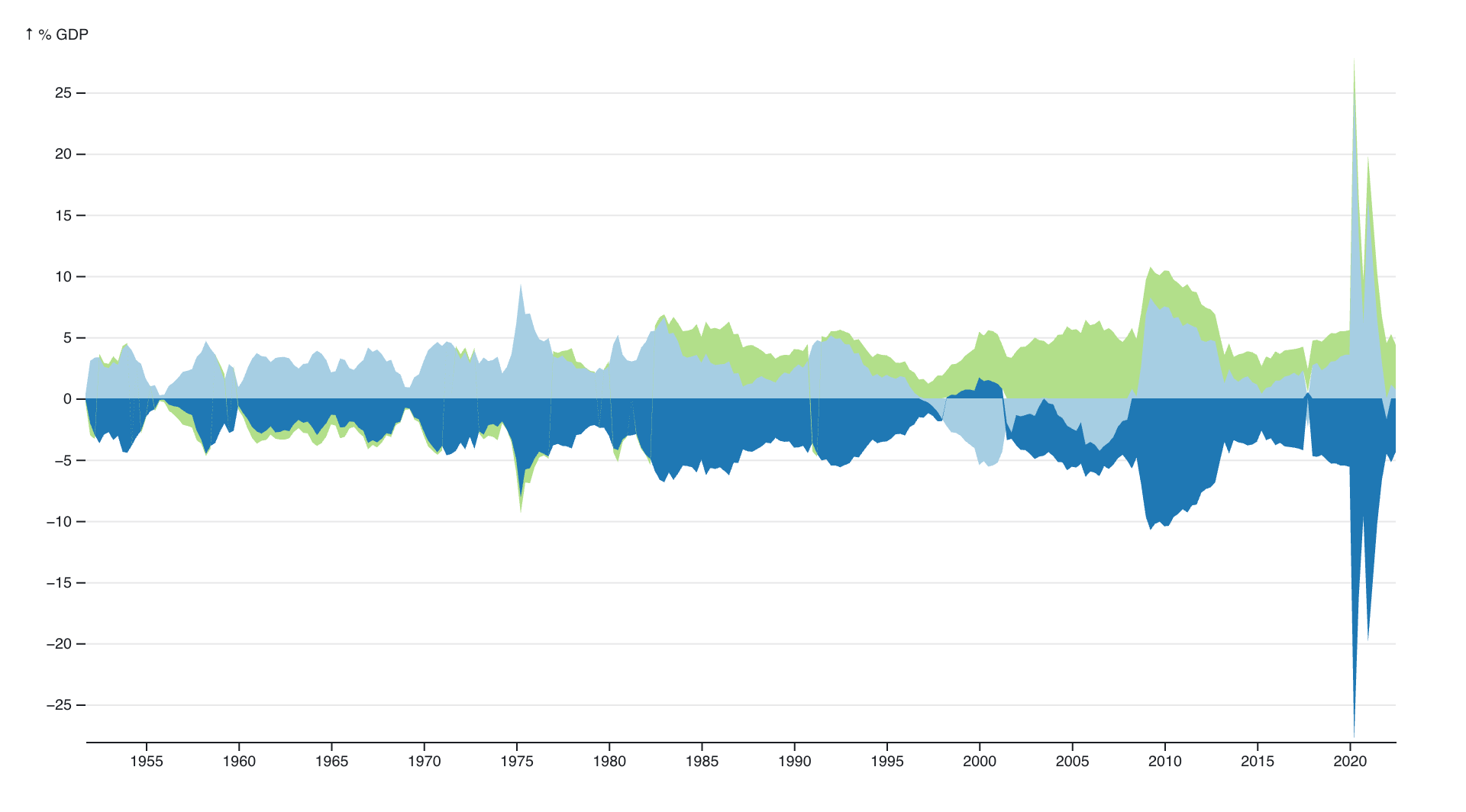

The interest rate settled at the price that allowed the entire banking system as a whole to meet its reserve requirements. Put another way, the interest rate was a function of the total reserves or the 'money supply'[4] in the banking system at the Fed, and changes in the interest rate reflecting changes in the total amount of reserves in the system were called "reserve effects". All else equal, when the Treasury transacts with the private sector in exchange for goods and services, the total balance of reserves in the banking system increases; when the Treasury taxes money out of the private sector, the total balance of reserves in the banking system decreases.

- If the banking system is flush with reserves such that all of the banks have plenty of reserves to meet their legal requirements, the interest rate will tend towards 0% as there will be few bidders willing to pay interest to borrow reserves.

- If the banking system lacks enough reserves to satisfy the legal requirements of all individual banks, then the interest rate will skyrocket.

- If the banking system has just more than enough reserves to satisfy all of the banks' reserve requirements, the price of borrowing reserves will be positive but not excessively high.

If the Treasury were to spend new reserves into to the banking system all willy nilly, the system as a whole would be flooded with an excess supply of reserves which would send the federal funds rate into a nosedive towards 0%. On the other hand, if the Treasury withdrew too many reserves from the system all at once as taxes were paid, the banks would end up overshooting the Fed's target interest rate by a long shot. A mismatch of inflows and outflows of reserves in the banking system would introduce chaotic price swings in the overnight lending market, adding a lot of noise to the signal the Fed is trying to transmit through its target interest rate.

[3] Nowadays, the target interest rate is achieved in a much less roundabout way with two different administered rates. (hat tip Ryan Benincasa of the Applied MMT Podcast & James Keenan of the MMT Google Group)

[4] This term can mean different things to different people. In this post, 'money supply' is used as a colloquial reference to the total amount of reserves held at the Fed.

Stabilizing the Interest Rate

For over 160 years, the US Treasury and central bank have worked together to smooth-out these reserve effects by maintaining a total balance of reserves within that Goldilocks zone that allows bids in the overnight lending market to remain right around the Fed's target rate. There are two key strategies that allow for stable short term interest rates:

Strategy #1: Avoid draining reserves all at once

Reserves extracted from the private sector via tax revenues as well as proceeds from (some) bond sales can be stored in "Tax & Loan" (T&L) accounts at private banks, thereby deferring the net-loss of reserves that would otherwise introduce an inflationary bias on the interest rate.

Strategy #2: Steady the Treasury's reserve balance

Simultaneously, the second objective is for the Treasury to maintain a "reasonably constant" balance at the Fed. In 1992, the goal was to maintain a reserve balance of $5B in Treasury accounts by transferring money to and from T&L accounts. If the Treasury anticipated the payments and receipts on its accounts at the Fed to net-out to an increase of $1B on any particular day, the Treasury would transfer $1B from its T&L accounts at private banks to its own account at the Fed in order to avoid a deflationary bias on the interest rate. Hitting the goal on the spot is extraordinarily difficult to achieve "because the payments coming into/going out of the Treasury’s account at the Fed can never be precisely known in advance" on any given day, much less on days with a high volume of tax receipts.

To see the Fed's track record, check out Figures 4 and 5 in Section 3: Strategies for Reducing the "Reserve Effect"

Where did the US Treasury get 6.1 trillion dollars?

It's Taxpayer money, right?

Well, no. Kelton notes that "taxes are not necessary for, or even capable of, financing [federal] government spending." The fact that reserves are gradually drawn from Tax & Loan accounts (where much of the tax revenues are deposited) as new government spending introduces new reserves into the banking system is not a matter of finance— it's simply an artifact of the accounting protocols that allowed the Fed to maintain an aggregate level of reserves that would yield the targeted Federal Funds Rate.

Tax revenues cannot finance government expenditures as "Federal Reserve notes (and reserves) are booked as liabilities on the Fed’s balance sheet and that these liabilities are extinguished/discharged when they are offered in payment to the State." In other words, once tax revenues are credited to the Treasury's account at the Fed (either immediately or after some time in a Tax & Loan account), those reserves are wiped from the financial scoreboard. That final transaction marks the end of those dollars' lives as the Treasury has no use for its own liability (promise) once it is returned to itself. Those dollars have done their job and, they've gone right back where they came from.

But don't worry, the Treasury has a virtually limitless supply of promises it can issue (obviously there are practical limits) and new reserves (promises) will be created and spent into the private sector anytime a check is written on the Treasury's account per the legislature's directive.

In sum, tax revenues aren't a means to finance expenditures at the federal level —the government doesn't want your money (its own promises) that only it has the legal authority to create. The government wants the things that the currency can buy from the private sector; the physical resources and efforts required to advance the public purpose. Taxes are a legal liability imposed to generate demand for the government's currency, and this demand plays a fundamental role in determining the purchasing power of the government's currency.

Is the money borrowed from bondholders?

Not quite. Revenues from the sale of Treasury securities don't actually supply any new reserves. Rather, "reserves are drained [...] when the Treasury issues bonds (immediately if T&L credit is not allowed or with a lag as the proceeds are transferred from T&L accounts)." By extracting dollars from the private sector through the sale of treasury securities, the government was able to "provide the private sector with an interest-earning alternative to non-interest-bearing government currency and allows the government to spend in excess of taxation while maintaining positive overnight lending rates."

What's more, is that when the Fed (the government) buys these securities form the Treasury (also the government), the transaction provides no new net reserves as both sides of the government's balance sheet are credited with the same amount —the Treasury liability is offset against a Federal Reserve asset and thus 'cancelled out'. This transaction is simply "an internal accounting operation, providing the government with a self-constructed spendable balance."

Kelton elaborates that while "self-imposed constraints may prevent the Treasury from creating all of its deposits in this way, there is no real limit on its ability to do so. The Federal Reserve was, for a time, prohibited from purchasing bonds directly from the Treasury. This changed during WWII, when the Fed was authorized to purchase up to $5 billion of securities directly from the Treasury. Since then, the limit has been raised several times."

So, where does the money really come from?

After considering the mechanics of the Fed's impressive accounting tactics that were once a logistical prerequisite to maintaining a stable rate of interest, it becomes readily apparent that nobody is magically supplying the Treasury with vast amounts of cash that only it has the authority to create.

The paper's clear view of reserve accounting operations reveals that "all [federal] spending is financed by the direct creation of [money]" and that "bond sales and taxation are merely alternative means by which to drain reserves/destroy [money]."

So, those 6.1 trillion dollars we've spent this year?

They didn't come from anyone —not taxpayers, not bondholders. It's just the public money that the Treasury creates as it spends reserves into the private sector.

TL;DR*

- Taxes and bonds cannot fund government expenditures; they can only drain funds from the money supply

- All government spending is 'financed' by the creation of new money by simply crediting private sector accounts at the Fed.

- For over 160 years, the US federal government administered a short-term interest rate by controlling the 'money supply' at the Fed, an approach that required using taxes and bonds as a means to offset increases in aggregate reserves from government expenditures. That approach to setting the interest rate was deprecated in 2008 when the Fed began paying interest on reserve balances.

*too long; didn't read

feedback | consulting | media | philanthropy

Brought to you by our sponsor